There’s certainly no shortage of advice for startups wanting to pitch investors for funding. So why would I offer more?

Much of the existing advice I’ve seen is very prescriptive – telling you what to say, what slides to include, even what size typeface to use….without necessarily explaining WHY.

For virtually any presentation, the better you understand your audience, the more effective your presentation will be. That’s certainly true for investor pitches too. But this does not mean “telling them what they want to hear.” In fact, remaining honest and ethical will create the best long-term win/win situations.

Following are the three key perspectives you must understand about investors if you want them to invest in your venture.

Context

But first, let’s set some context:

- Investor: By “investor”, I’m referring primarily to economic investors – those investors who are seeking the best economic returns from their investments (as opposed to say philanthropic investors who may have other priority objectives).

- Presentation: I’ll focus primarily on giving a slide presentation, but really these points can be applied to almost any means of communicating your pitch. I often only half-jokingly say that if you have your story down (logical convincing story + concise compelling language), you should be able to pitch effectively literally on the back of a napkin.

- Teaser: This is assumed to be your first pitch to select prospective investors. So, the goal is to get them interested enough to have another meeting. Think of it as a “teaser,” or “hooking the fish.” Don’t try to convey everything. You usually do not need financial projections or a demo (even during most “demo day” pitches). You want to communicate as much as needed, but as little as possible to remain concise. Understanding investors’ key objectives will help a lot here.

- Duration: 4-5 minutes is about as much as you can expect a prospective investor to spend initially to determine if they might be interested. This is similar to the time you would have when presenting at a typical accelerator’s demo day.

Alignment

Whether explicit or not, I often get the vibe that startup founders view investors with a bit of an adversarial bias. Like they’re trying to “get” money from investors. Again, there are always exceptions, but if your goals include economic gain for yourself, then you are probably more aligned with investors than you realize. Keep this in mind. They may be critical of how/where/with whom they invest their money, but so should you about how/where/with whom you invest your time. When you better understand the investor’s criteria, you’ll realize you probably should be including similar criteria yourself.

Investors’ Criteria

I often hear entrepreneurs explain why they need money. Too frequently, they may seek investment to pay off some debt or pay themselves salaries. Investors don’t want to hear why founders need money; investors want to hear how you will make them more money. They want to know that the money they give you will go directly towards activities that will multiply their money.

In academic speak, economic investors want a combination of two fundamental things:

- Highest Expected Value (EV), and

- Highest Net Present Value (NPV)

Expected value is the value of an outcome multiplied by the probability of that outcome. For example, a 10% probability of making $1,000 has an EV of $100. A 1% chance of making $10,000 has the same EV of $100. The point here is that investors want to maximize both numbers. The greater the potential outcome and the greater the probability (i.e., lower the risk), the greater the return on their investment.

But there’s also a time factor, or a “time value of money” (TVM). A gain returned in 1 year is more valuable than the same gain returned in 2 years, because there is an opportunity cost (and additional risk) of that second year – i.e., the money returned after year 1 could be invested (somewhere) for additional return during the second year. For example, if you could receive $100 return after 1 year, and use say 5% as the opportunity cost (the high probability return you can safely get investing elsewhere), then you should expect to receive $105 return after 2 years to be equivalent to receiving $100 a year earlier (excluding additional risk).

Your Pitch

So how do we apply this (EV and NPV) to our investor pitch? Investors essentially want to see 3 main things in an investment opportunity: 1) large opportunity, 2) best timing, with 3) the least risk. Keep in mind that an investor is not necessarily comparing these three metrics with investments similar to yours. They are comparing these three metrics for all investment opportunities they may consider. Thus, you must optimize these to rise to the top of that larger list.

1. Opportunity

Obviously, investors want to see a large opportunity. However, your estimate must be credible.

Founders often make the mistake of intentionally or accidentally over-estimating their opportunity or total addressable market (TAM). As a simplistic example, if you’re selling a new artificial coffee sweetener, your TAM is not all coffee sales; and it may not be all coffee sweetener sales (e.g., if you’re unlikely to convert many natural sugar users). Top-down estimates like this also tend to come across as academic with too much handwaving to be credible.

Bottom-up estimates may simplistically start with price per unit and multiply by number of potential unit sales. However, this assumes the price per unit is valid and can be maintained over time. For example, if you’re selling facial-recognition software at say $100/year for 10M existing video cameras to show a $1B TAM, you’d better show proof you can get $100/year (e.g., existing sales, and/or very clear ROI that’s greater than $100/year).

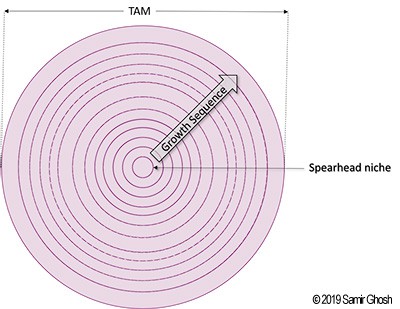

Investors, as should you, prefer to see you tackle a targeted niche. This improves your chances for success because you can focus on satisfying the unique needs of that niche, you have to beat fewer competitors, and your GTM (go-to-market) can be very targeted. Ironically, however, investors want to see a large opportunity. How do you satisfy both? See my “TAM Onion” blog post for how to address this. The context for the details in the rest of your presentation should focus on your spearhead market.

Investors, as should you, prefer to see you tackle a targeted niche. This improves your chances for success because you can focus on satisfying the unique needs of that niche, you have to beat fewer competitors, and your GTM (go-to-market) can be very targeted. Ironically, however, investors want to see a large opportunity. How do you satisfy both? See my “TAM Onion” blog post for how to address this. The context for the details in the rest of your presentation should focus on your spearhead market.

2. Timing

There are 3 key questions you want to answer regarding timing:

a) Why hasn’t this problem been solved before?

If you’re answer is “I don’t know” or “because we’re smarter than everyone else,” you will probably come across as naïve. The investor’s conclusion will probably be that you simply don’t know all the pitfalls that await you, so they’ll wait and see.

b) Why is a solution to this problem inevitable?

What external changes or increasing pains (e.g., new regulations, competition, resource scarcity, increasing expense) and/or reducing barriers (e.g., new technology, device adoption) are bringing this to a head? Ideally, there is a “perfect storm”, or combination of forces that make some solution to this problem virtually certain.

c) Why will this happen quickly?

The longer it will take for an opportunity to appear, grow, or for you to capitalize on it, the less desirable the investment. Remember the time value of money (above). It’s virtually always better to get money back sooner than the same amount later. And perhaps as significant is the increased risk over time. External forces could change, markets could change, founders could get hit by a bus.

3. Risk

Investors want a large return, quickly, and…at the least risk. But this risk bucket has a lot of items, e.g., Product risk, Technology risk, GTM risk, Competition risk, Financial risk, Market risk, Regulatory risk, Environmental risk, Execution risk, Team risk, et. al.

The more you lower these risks, the greater the expected value, or potential return for investors. Thus, “traction” is usually the best proxy for demonstrating you’ve reduced these risks. However, traction does not just mean revenue. Ideally, your traction should demonstrate as many key areas (assumptions, risks) of your business as you can. For example, maybe you can brag about customers; but how did you get those customers? Did you acquire them by validating the go-to-market channels your business plan (hypothesis) is relying on to scale?

Presentation Outline

Lots of presentations open with a description of the team, or a moving story about the founder’s journey. These may be appropriate things to convey. However, I would argue that the timing/sequence may not be right. As always, consider your context. Does your investor audience see lots of pitches? In a Demo Day pitch, they may see a lot of pitches in one day.

The harsh reality is that investors do not care about you or your company UNTIL they care about the investment opportunity…the business.

Thus, I strongly suggest you consider thinking about your presentation in 3 sections: Business Hypothesis, It’s Real, and The Future. Following is my proposed presentation slide outline, grouped by these sections. The order of some slides may change depending on your situation. For example, if your GTM is a unique strength, then you may want to move it closer to, or combine with your Differentiation slide.

Business Hypothesis

Convince prospective investors FIRST about the hypothetical business opportunity. If you hook them about the opportunity, then, and only then, will they care to learn more about your company.

Slide 1. Title

Include a 1-line description of your business. Again, remember your audience. This does not need to be your creative tagline intended for customers. It should include what you are and for what market. E.g., Investors should be able to clearly tell whether you’re a software or hardware company targeting B2B or B2C. If you leave them guessing, they may tune-out early. Give them the context quickly. As an analogy, you live in a tiny part of a forest. Your audience does not even know if you live in a forest, desert, underwater, or outer space.

I would suggest a format something like “[What it is] provides [Benefit] to [Whom].” And I would suggest addressing the larger TAM rather than just the spearhead since you’re pitching the big opportunity – e.g., “Mobile App That Reduces Restaurant Cancellations by 50%”.

If you truly envision a larger disruption opportunity, describe it in your title. Reference points are helpful, but caution — “The Uber of abc” and “the AirBNB of xyz” have been overused. If you do use a reference point, use it correctly. E.g., Don’t call yourself the “LinkedIn of xyz” just because you’re a professional directory but your business model is completely different.

Slide 2. Problem

State the problem, the pain or pleasure point and for whom. Be specific.

Opening with a story can be engaging, but remember, the prospective investor audience does not care about you…yet. However, illustrating your market’s pain can be great fodder for an opening story.

Qualify the severity of this problem for one theoretical customer. Is this problem relatively big enough and urgent enough for a customer to invest their time, mindshare, and money to resolve it?

For B2B (business-to-business) markets, convey this as costs or opportunity costs (e.g., potential new revenue). See my Business Value QuadArrow for a comprehensive way to think about all the value your solution may provide to one customer. The QuadArrow is focused on B2B but can also be applied to B2C (business-to-consumer) market businesses. In B2C, besides monetary savings, consider other benefits, especially emotional benefits to customers.

Slide 3. Solution

Don’t go into too much detail here. E.g., Make sure audience knows whether your solution includes hardware, software, and/or services. Remember, this is a teaser pitch; you do not need to include every detail about your architecture, tech stack, etc. Make sure they know what your solution is and the main way it is unique from competitors.

Quantify the benefit to your customer (this could also be done in the following Business Model slide to clearly justify your price). Founders often make the mistake of thinking any improvement is worth it to customers. That’s not true. Change, even for the better, comes with cost and risk. Customers may have to learn something new, or spend time setting up your solution. Potentially worse, if your solution fails them in some way, they may lose their job (B2B) or damage an important relationship (B2C). Thus, your solution better provide significant (e.g., 100%+, not 10%) improvement over at least their status quo, and ideally, all alternatives.

Slide 4. Business Model

How will you make money? Initially and at scale?

Who specifically pays? Don’t confuse the buyer with the user or an influencer.

For enterprise startups: Be very specific about which business unit, whose budget, even down to which line item within the budget. This is important to understand. If your typical customer has no clear line item budget, then every sale may require getting a budget added, which is difficult and could easily require waiting for a new budget cycle (e.g., a year). If there is a line item budget, then you will be taking budget away from something else – i.e., your customer will not be able to purchase what the budget was intended to purchase. You’ve got a problem if that “something else” is more critical to the customer than your product.

Slide 5. Opportunity Size

How big is this opportunity? If you can show that even your “worst case” scenario is a big market, even better. General rule-of-thumb: institutional VCs want to see at least $500M realistic TAM. Use my TAM Onion to show a thoughtful plan by segmenting, and sequencing markets that will lead you to a large TAM.

Slide 6. Timing

- Why Now?

- Why Inevitably?

- Why Quickly?

(see above)

Slide 7. Differentiation

A picture is worth a thousand words. I really like perceptual maps (i.e., simple X/Y axes) or 2×2 matrix like Gartner’s “Magic Quadrant.” The key is to pick two key benefits your customers value highly that will separate your company into the top right quadrant from your competitors.

Unless your competitors are obvious to the audience, there’s no need to list actual competitors. Instead, group them into categories and plot one point for each category (not competitor).

Be sure to include the status quo. How are they solving the problem today? For example, if you’re introducing the first motor scooter to a market that only rides bikes, don’t show only scooter competitors; include where the bike fits in your matrix.

Slide 8. GTM

Go-to-market is arguably greater than 50% of the success equation. The startup landscape is littered with dead companies that had superior products. However, if you cannot reach your customers and convince them to buy, then a business you do not have. Every scalable business must have an efficient GTM. In fact, many of the most successful startups you can probably think of had GTM strategies as innovative as their products. Unfortunately, however, most founders spend far too little attention on GTM. Answers like, “advertising” or “direct sales” are so vague and potentially expensive that they come across as naïve.

Use the TAM Onion to sequence your target segments. Then, your GTM tactics can be specific and cost effective. However, for a teaser deck, you only need to convey your GTM strategy for your spearhead market. Save details about subsequent markets for future meetings.

It’s Real

If you got their interest about the potential opportunity, now is your chance to knock them over the head with your execution (your ability to execute and advance the business). A la: “Not only is this a great investment hypothetically, but we’re actually already doing it.” Show your traction to do so.

Slide 9. Traction

Consider what successes demonstrate effectiveness of your plan. For example, show that you can fill the top of your funnel with leads and move them down the funnel. Claiming revenue and paying customers may sound good, but savvy investors will ask how you acquired those customers. If you acquired enterprise customers through warm connections only, then you have not demonstrated that your GTM strategy will work on cold leads and scale. If you acquired small customers because the sales cycle was faster, but your business hypothesis is based on large enterprise customers, it might in fact be better to show progress, even if not closed sales, with target enterprises.

The Future

Now, if they’ve bought into your theoretical opportunity, and they’re impressed with your progress, this is your chance to knock them out with your team. The only thing I guarantee founders is that their business probably will not go exactly as planned. Savvy investors know this too; that’s why so many investors consider the team to be most important.

Slide 10. Team

If the team or key founder has stellar credentials (e.g., technical notoriety or big startup successes), then it may make sense to lead your presentation with the team to get the audience’s attention. However, in general, demonstrate how you’ve built a great team to take the company forward.

Highlight notably past employers and universities. Logos work well but include versions with text in case someone does not recognize the logo. Include advisors but be clear to distinguish them from company team members. Don’t include anyone without their permission or who may not give positive feedback. You never know whom in your audience may know an advisor you list. And with permission, include notable investors; they can add credibility.

Tips

In addition to the above rationale for better understanding economic investors, and proposed pitch outline, below are some general pitch tips.

a) Build Your Story First

Don’t start by creating slides.

The temptation is to get your presentation done quickly, and pretty designs help make anything look better. But really, your story needs to stand on its own. It needs to be compelling in its rawest, black & white text form. Once you get too invested in building slides, graphics, etc., it becomes harder to make the substantive changes that are really needed.

Along those same lines, start with a word-stingy outline first. When satisfactorily revised, use it to derive all your pitch deliverables from elevator pitch to investor leave-behind to live pitch deck.

An outline also makes collaborating with others on the story far more effective. If you start with slides, then the reader has to reverse-engineer the intended story, and then they can never be sure if you wrote something that does not convey what you intended vs you intended the wrong thing.

b) Minimize Text

In a presentation, each slide should convey one key point. Leverage graphics to convey your message. Too much text distracts the audience away from you and/or won’t get read anyway. There’s tons of public advice on this.

c) Branding

Always have at least your company name & logo on every slide. You never know when an investor may physically or mentally tune in or out of your presentation. If they like something in the middle, you want to make sure they know it was you.

d) Hypotheses

You don’t need to have proof for everything. A startup is a business hypothesis with many assumptions. Reality (data) is better, but without it, start with “educated guesses.” Your job as a founder is then to test those assumptions.

e) Web-hosted

Provide your deck via a link to a hosted deck (e.g., DocSend or DocSketch) for a few reasons: 1) you can track who/when/how much someone reviews your deck, 2) a cloud version is always the latest version (i.e., you can update it as needed), 3) it limits the sharing out of your control. You’ll get some folks who insist you email a PDF attachment. These services allow you to create a different link that allows download.

f) Multiple Decks

Just as you should not create one deck for customers and investors, don’t expect to use the same deck as a leave-behind for investors and to which you present live. Of course, it’s more work to maintain two decks, so an easy hack: maintain Speaker Notes that explain each slide for investors and print “Note Pages” (in PowerPoint) to PDF. Caution: You’ll have to remember to never include any notes that an investor should not see.

g) Delivery

Don’t memorize a script; just remember to make the key 1 point for each slide.

I used to train new triathletes as a triathlon coach for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s “Team in Training” program. Triathlon is a complicated sport involving 3 sports, various rules, equipment, and strategies. All of that can be overwhelming, so I instilled focus in 3 things to complete a race which worked quite well (for another post).

Similarly, a focus on the three key investor objectives (Opportunity, Timing, and Risk) helps guide founders when pitching their startup while fundraising. I put together a PowerPoint template to help you get started:

Please let me know if this blog post has been helpful.

Excellent resource, Samir. I especially like the way you have broken down the various key areas that startups need to address in their pitches, and then further breakdown each of those into actionable chunks. Clear and easy to understand – startups would do well to follow your approach.

Thanks Tom! That means a lot coming from you.